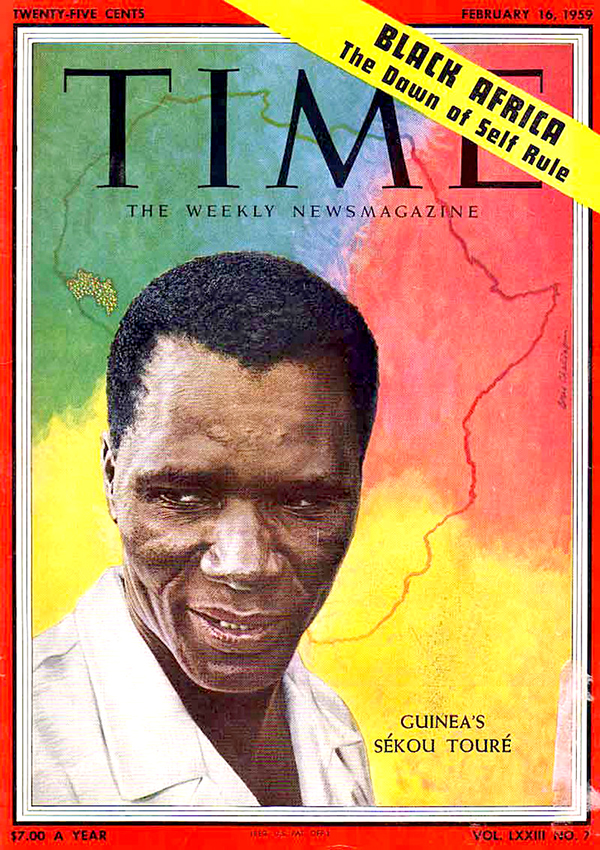

Sékou Touré

Vive l'Indépendance !

Time, february 16, 1959. pp. 24-30

On the hot, dusty football field just outside Conakry. the graceful, black-skinned Guinea women danced tirelessly, sinuously. Blue silken turbans, spangled with gold flashed in the blazing sun as they stomped, glided, clapped their hanfds and leaped about. The clanking of the xylophones rose to fever pitch, then died away. Three griots (West African minstrels) —one in a leather cape adorned with bits of mirror, another carrying a musket, and the third strumming on a one-string gourd guitar-wailed out a chant in honor of the man who for two solid hours had been. the center of all the attention. Finally, Sékou Touré, 37 President of the new Republic of Guinea, a trim figure in a European busine suit, rose and raised his arm.

“Vive l'indépendance!” he shouted,and three times the crowd roared back, “Vive l'indépendance!” “Vive l'Afrique!” he shrieked in a voice close to frenzy. Once again, the cry was three times repeated. There was no reason for Touré to do more. The crowd had een and heard him, and that was enough.

Needed: New Maps

Broad-shouldered and handsome. Sékou Touré is as dynamic a platform performer as any in all Black Africa. He is the idol of his 2,500.000 people, and the shadow he casts over Africa stretches far beyond the borders of his Oregon-sized country. As the head of the only French territory to vote against De Gaulle's constitution and thus to choose complete independence, he has been suddenly catapulted into the forefront of the African scene. Last weeek somnolent, picturesque Conakry was getting to know how it feels to be the capital of an independent nation. France, Britain and the U.S. were busy setting up embassies; there had been trade missions from East Germany, Poland and Czechoslovakia; and last week the first ambassador arrived—from Communist Bulgaria. When Touré decided to say no to De Gaulle, he cut adrift a land that has only 200 university graduates, a literacy rate of 5%, and an average annual income of most peasants of about $40. But Africa today is in no mood to be practical. Guinea's big gamble was just the thing to capture the imagination of 185 million blacks plunging headlong toward independence. As week after week the drive picks up momentum. Africa seems in perpetual need of new maps. When Touré was born Liberia and Ethiopia were the only independent states on the continent. Today there are another eight—Egypt, the Soudan, Libya. Morocco, Tunisia, the Union of South Africa, Ghana and Touré's own Guinea. In the land known as “Black Africa” four more territories—the Cameroons, Togoland, Somalia and the vast land of Nigeria, Britain's biggest colonial possession-will be free by 1960.

Hurry, Hurry.

In Paris last week the Premiers of twelve former French African territories met with De Gaulle for the first time as heads of autonomous states within the French Community-and everyone present was mindful of the missing man, who had decided to go it alone: Sékou Touré . In Britain's domain, Prime Minister Sir Roy Welensky of the Central African Federation (Nyasaland and the two Rhodesias) has been plumping for indepindence within the Commonwealth by 1960. Even Belgium, which until 1957 denied the vote to both blacks and whites and relied on efficiency and prosperity to keep the natives quiet in the rich Belgian Congo, has promised to move “towards independence without fatal delays but also without inconsiderate haste.”

The hard fact is that haste is just what the Africans want. Nyasaland echoes with the fulminations of Dr. Hastings Banda (“To hell with federation!”) and the cries of “Kwaca!”, meaning the dawn of freedom. Kenya's smart, articulate young Tom Mboya was not speaking for his country alone when he bluntly told the Europeans to “scram from Africa.” There have been riots in Nyasaland, and the recent bloody eruptions in the Belgian Congo tore away the last shred of illusion that economic paternalism is enough to stem the tide.

Today, Black Africa seems to be getting a kind of Mason-Dixon line of its own. Down East Africa and across the bottom of the continent runs a high plateau (4,000 ft. to 6,ooo ft.) from Kenya to Cape Town, in this area lives the bulk of Africa's white or “European” population, as well as half a million Asians. Whites. with black labor, have built and settled these lands, and are determined to stay there, and to stay in control. The militancy of their views increases, as does the density of the white population, the farther south the traveler goes, climaxing in the dour and relentless apartkeid of the Union of South Africa.

“Poor Sékou.”

The black men, mainly in the west of Africa, who are leading their illiterate millions to freedom talk mystically of an eventual United States of Africa and of something called the African Personality. Their own personalities range from the demagogic Dr. Banda and the French Congo's Premier Abbé Fulbert Youlou, who is not above “blessing” ballpoint pens and then selling them to gullible schoolboys just before exams, to Senegal's erudite and sophisticated Léopold Sédar Senghor, poet and lion of the Paris salons, who said upon hearing of Sékou Touré s vote of no: “Poor Sékou. Never again will he stroll up the Champs Elysées.”

Guinea women and girls working on a “human investment” project. (F. Gigon)

The purest gold, a kind of grass, a species of hen and an urge for haste.

Part dedicated idealist and part ruthless organizer-perhaps the best in Black Africa-Guinea's Touré should have problems enough just coping with the disruption that inevitably came with independence. But he, too, has dreams as wide as a continent. “All Africa,” says he, “is my problem.”

In a sense, he was born in the right place and with the right ancestry to favor a big role. Though Africa was, until the Europeans came, the continent that could not write, it had known its times of glory.

Guinea was once part of the powerful Mali Empire that stretched from the French Sudan, on the upper reaches of the Niger, to just short of West Africa's Atlantic Coast. When its 14th century ruler, the Mansa (Sultan) Musa, made his pilgrimage to Mecca, he traveled with a caravan of 60,000 men, and among his camels were 80 that each bore 300 lbs. of gold. He built his wife a swimming pool in the desert, and filled it with water borne in skins by his slaves; he turned the fabled city of Timbuktu into a trading center and a refuge for scholars. But such medieval empires one by one faded away. Gradually the history of Africa became, not the story of those who lived there, but of men named Livingstone, Stanley, Peters and Rhodes, and of countless anonymous adventurers in search of gold, ivory and slaves.

Legendary Grandfather.

In 1815 Europeans began penetrating the thick forests of Guinea, which was to give its name to a coin of purest gold, a kind of grass, and a species of hen. Among them was a young Frenchman named René Caillé, who, dressed as an Arab, talked of his captivity by the Egyptians. was accepted as a Moslem and was able to make his famed journey safely to Timbuktu. After him other Frenchmen came, and eventually, by the “rules of the game” 1 laid down by the Berlin Conference of 1884-85 for spreading civilization throughout darkest Africa, French hegemony over the area was recognized. The “scramble for Africa” was on, and there was little the Africans could do about it.

One man who did was Almamy Samory Touré, who pledged himself to an enemy chief and became a slave so that his captive mother could be released. Like the Biblical Joseph, he rose to head the enemy tribe, fought the French until 1898 when he was captured. The French swarmed over French West and French Equatorial Africa and Madagascar—an area 14 times the size of France. But the legend lived on of the warrior Samory, whom Sékou Touré claims as his grandfather.

The Troublemaker

Aside from this lofty connection, Touré's childhood was singularly unmajestic. One of seven children of an impoverished peasant farmer, he attended a school of Koranic studies at Kankan, eventually wound up in a French technical school. Even after he was forced to quit school, he nagged his friends who were still going to tell him what they had learned, started to read everything he could lay his hands on. In time he became a French colonial treasury clerk in his own country, but his real interests were something else. When the treasury tried to muffle his shrill union talk by sending him to a post outside the country, he quit and became fulltime head of the Guinea branch of France's Confédération Générale du Travail. French officials have vivid memories of the Touré of those days. “He was impossible,” says one. “Always making trouble.”

At that time the trade union movement of France was Communist-controlled, and the Communists began taking an interest in the young man who wore those smart European suits and could hold an audience spellbound for hours, whether speaking, French, his own native Malinké, or Soussou, the language of the singing and dancing people of the coast. Touré was brought to Europe, visited Warsaw and Prague, came back spouting Marxism. The founder of Guinea's first labor union, he was the power behind the strikes of 1953, which brought to French African workers their first major concessions. The workers' hero, he began to take on that mystical aura so valuable to African leaders. Once, when a political opponent happened to drop dead a few days after Touré attacked him in a speech, word went around that the tongue of Touré had the power to kill.

[Note. However, another rumor run through Guinea that the death of veteran politician Yacine Diallo —it was him— was not a supernatural incident; instead, it was the result of foul play in the form of criminal poisoning. People still believe, today, that Sékou Touré, himself, was implicated in the sudden death of a formidable challenger. André Lewin's has written an account of the legislative sessiom during which Diallo and Touré clashed verbally. Yacine died that night. — Tierno S. Bah.]

Full House

In the days when Touré was just beginning to emerge, the most powerful politician in French West Africa was Fé1ix Houphouet-Boigny, and to this day Houphouet-Boigny is the strongman of the rich Ivory Coast. He organized the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (R.D.A.) as a popular front for various French African political parties, which in Paris voted with the Communists. Young Touré was at his side in the R.D.A. Already a power in labor, Touré now became a formidable figure in politics. He rose from membership in Guinea's legislative assembly to mayor of the capital city of Conakry (pop. 70,000), and finally to Deputy in the French Assembly in Paris, where Houphouet-Boigny already sat. There, Touré began his maiden speech to a Chamber empty except for a few members buried in newspapers. As he spoke, the newspapers were dropped, the absent Deputies began filtering back to their seats. By the time he had finished, the Chamber was full.

Already Touré was beginning to grow apart from his older colleague from the Ivory Coast. Houphouet-Boigny, now mellow with the years, broke with the Communists, came to be regarded by the French government as their indispensable African; he was laden with honors, the one African usually included in every French Cabinet. Touré reorganized Guinea's R.D.A. along Marxist lines. He set up a powerful new union (700,000 members) free of Paris direction both Communist and non-Communist, stomped out all opposition at home, and at times resorted to burning the homes of those who stood in his way. He had become the most powerful man in Guinea. When France put through the Loi-cadre in 1957, which kept control of each territory in the hands of a French governor but gave Africans the right to elect their own No. 2 man as vice president of the Executive Council, Touré was ready.

Under the law his powers were limited, but no one could have made more use of them. Like Ghana's Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah, who has waged relentless war against the traditional tribal power of the Ashanti chiefs in his homeland, Touré tackled the tribalism that plagues all of Africa. He summoned the French commandants de cercle—the French equivalent of the British district commissioners —asked them what they thought of the chiefs who were running Guinea's 240 cantons. The commandants were delighted to help: this chief was lazy, that one corrupt. As a matter of fact, the whole cantonal system had degenerated into a kind of feudal thievery that was costing the government at least 400 million francs ($1,140,000) a year. With his devastating list of particulars in hand, Touré summarily abolished the chieftaincies. When the chiefs howled, he published the French list of charges against them. When the French officials howled in turn, it was too late.

With the chiefs out of the way, he set up more than 4,000 village councils, elected by universal suffrage. This grass-roots democracy was something new to French Africa, and in the hidebound Moslem region of Fouta-Djallon even some women got elected. “The election of women, griots and former slaves,” declared Touré expansively, “is the mark of a veritable prize of political conscience, a spiritual revolution.”

For a while, Paris forgot its former misgivings about Touré and beamed with satisfaction at the progress that the little country of rivers, steamy swamps, rocky hills and dry savannahs seemed to be making under its Marxist leader. Since De Gaulle's wartime days as the Man of Brazzaville, when the colonies rallied to his cause, France had been taking a new interest in her southern empire. While, before the war, the whole of French Africa got only one-eighth of what France poured into her other overseas territories, it has since received more than $2 billion. Of that, $79 million has gone to Guinea.

The End of Assimilation

The Loi-cadre was in itself a revolutionary move in French colonial thinking. It meant the end of the concept of a French republic “one and indivisible” and of the tradition of cultural “assimilation.” But for all France's concessions, and for all the money it belatedly spent on schools (there are still only 250 in Guinea), on building the port of Conakry, on roads and on the battles against such scourges as malaria, sleeping sickness and leprosy, Touré made no secret of the fact that he regarded the Loi-cadre as only “a first step in an irreversible process.” He even went to Paris to discuss “the next step,” and when told that the new law clearly defined Guinea's place, snapped: “We are not here to be told what the law is. We are here to make the law.” Coming to power last May, Charles de Gaulle made his dramatic offer to the French African territories: they could have the choice between (a) complete independence, (b) autonomy within the French Community, or (c) the status of a department of France. Touré charged that the whole idea of a French Community—which came close, but not close enough, to the British Commonwealth—would only continue “our status of perpetual dependence, our status of indignity, our status of insubordination.” When De Gaulle stopped off at Conakry on his swift tour of Africa before the referendum, Touré thundered in his presence: “We prefer poverty in liberty to riches in slavery.” Angrily, De Gaulle canceled a diner intime he was to have had with Touré, and the split was final. A few weeks later, 95% of the people of Guinea voted no to the De Gaulle constitution.

Go Away

“We do not wish,” Touré had said, “to settle our fate without France or against France.” But De Gaulle at first was quite willing to carry on without Guinea. Paris announced that all French functionaries would be withdrawn within two months. Touré's brash reply: Remove them in eight days. While French shopkeepers and businessmen stayed on, 350 officials and their families began moving out. French justice stopped. A ship heading for Guinea with a carload of rice went to the Ivory Coast instead. Radio Conakry temporarily went off the air. The Guineans charged that the departing French were taking everything—medical supplies, official records, air conditioners, even electric wiring.

The governor's palace was being stripped when Guineans found that some of the furniture that was to be shipped to France actually belonged to Guinea. Thereupon a comic-opera, two-way traffic began at the palace, with the French hauling things out and the Guineans hauling things in. When Touré and his willowy second wife (daughter of a French father and a Malinké mother) moved into the palace, they did not even have a telephone.

Madame Touré.

A palace without a telephone.

Though the people of Guinea rejoiced, Touré banned all demonstrations, announced: “This is no time for dancing.” More than any other African state, Guinea was on its own. The British had bequeathed to Nkrumah a prosperous Ghana. President Tubman, who runs Liberia as Boss Pendergast once ran Kansas City, has the Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. as the biggest employer in his land. The Sudan, after getting its independence, is calling back British technicians. Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia has Swedes training his air force, Indians running his state bank, Americans running the airline, and French Canadian Jesuits running the state university.

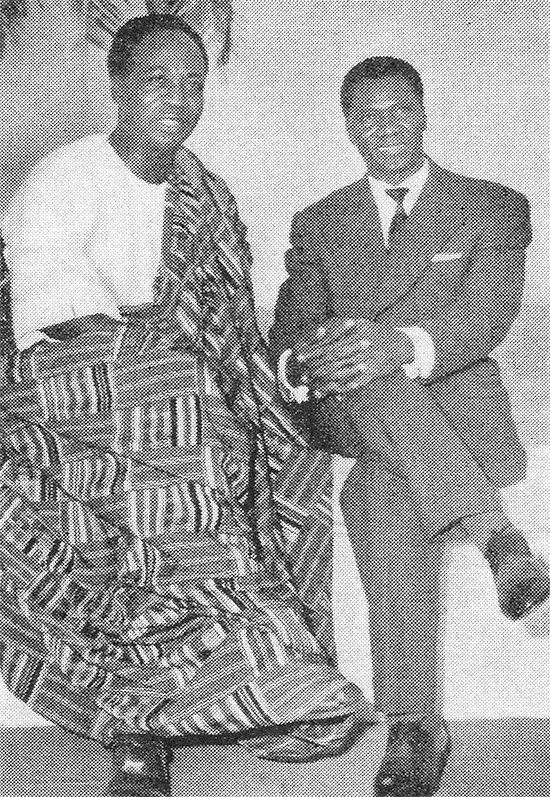

Ghana's Nkrumah & Touré (A.K. Deh)

Dowry: $28 million.

Over Conakry, a city of sleepy charm with its thick-walled, whitewashed houses, its cool green mango trees, its shops and bars that bear the stamp of France (Le Royal, St. Germain, A la Chope Bar, Chez Maître Diop), an air of harassed improvisation fell. For lack of help, ministers had to do the secretarial work while visitors clogged their waiting rooms. Telephones did not work, clerks scuttered about looking for the only copy of the diplomatic list. Messages were sent in to the Minister of Health while he was performing surgical operations.

“I am Everybody.”

Had it not been for the special talents of the man in the Presidential Palace, the newborn nation might have come apart at the seams. But Touré combines the Marxist genius for organizing with an almost mystical view of himself as the father of his people. He is most at home talking to village headmen, acts as if all their problems are his own. Though raised a Moslem, he now refuses to pin down his faith in public. “I am Protestant, Catholic, Moslem and fetishist,” says he. “I am all faiths. As President, I am everybody.” As a politician, he is everybody too.

Though no Soviet-style Communist, Touré rules his country not through government but through a single party. The 4,000 local committees of the Parti Dimocratique de Guinje (P.D.G.) provide one committee for every 600 men, women and children. Since the committees are freely elected each year, Touré boasts that his system is “total democracy,” organized “from the base to the summit.” “The government,” he goes on to explain, “has no role in the party. It is the party that has the role in the government.”

And what of Parliament? Says Touré's No. 2 man, President Diallo Saifoulaye of the National Assembly:

— “Parliament is an institution for the legalization of party decisions.”

— Why, then, should it bother to debate?

— “There is practically no discussion in Parliament. Discussion is for journalists.”

Touré is also showing a marked desire to trade with his old Communist friends. He has reached agreements with the East German, Czech and Polish trade delegations amounting to 30% of Guinea's normal foreign trade. They will get all of Guinea's palm kernel nuts, about half its bananas and coffee. The Soviet Union may buy the rest of the coffee crop. Last week Touré set up by decree a special state trading agency to handle his new business—a move that greatly distresses local businessmen, who fear that he wants to channel private trade through government agencies.

They Must Work.

In a desperate attempt to compensate for the loss of French services, Touré, who can get by with only three or four hours of sleep a night, began driving his countrymen as hard as himself. He is not nicknamed “The Elephant” for nothing. “Men of Africa must work,” he said. “In underdeveloped countries, human energy is the principal capital.” To the wild beating of tomtoms he inaugurated his “human investment program”—a campaign of “travail obligatoire” that bears a disturbing resemblance to the communes of Communist China, as well as to the corvée, or forced road labor, of the ancien régime in France. Actually, the program so far involves little more than innumerable local work bees in which a whole village will turn out to clean streets, cut back underbrush, make bricks for a new school. “A year from now,” Touré told his people, “you will no longer be able to see a single young Guinean girl, torso naked, carrying two bananas on a platter, going out to engage in prostitution. We have our will, our arms and legs, and we know how to work,” declared Touré grandly—but arms and legs were not enough. And so one day last November the President of Guinea flew off to pay a state visit to Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. The two men soon had both Paris and London gasping.

“Inspired by the example of the 13 American colonies,” they announced, they were forming a union of their two countries. The French press saw the whole deal as a British plot to undermine France's prestige in Africa. The London Daily Express asked just as indignantly: “Is Dr. Nkrumah planning to bring a foreign territory into the British family of nations?” Touré flew home with the promise of $28 million from Nkrumah.

Snuggle Up

Since then, surprisingly little has been heard about the union. So far the two countries have not even set up the constitutional and economic commissions they promised. Instead, Guinea has been snuggling up to France, which has gradually swallowed its indignation over the man who said no. Last month Guinea negotiated a series of agreements which to a considerable extent place the country squarely back in the French Community. It will:

- stay in the franc zone

- keep its foreign exchange in the Banque de France

- once again get technical assistance from France

[Note. The deal collapsed the following year with the creation of the Guinean Franc, March 1, 1960, followed a couple of months later by the Ibrahima Diallo Plot. This Time's article was published four months into Sekou Toure's presidency, who invented the expression “The Permanent Plot” and institutionalized a rule of terror and cyclical repression. The purges and the bloodletting went on unabated for the next quarter of century at Camp Boiro and elsewhere, until the dictator's death of heart failure in 1984, in Cleveland, Ohio.

Touré's military successors (Gen. Lansana Conté, Capt. Moussa Dadis Camara, Gen. Sékouba Konaté) sought to imitate his tyrannical policies, namely the systematic violations of human and constitutional rights. And Alpha Condé, the current and “democratically elected ” president, has been doing likewise since his 2010 inauguration, thereby further worsening the plight of post-colonial Guinea. — Tierno S. Bah]

In lands where it has no diplomatic representation, France—not Ghana—will speak for it. In four short months Guinea has apparently learned that independence is a relative thing. It will not be easy for Africa to be completely itself, for no other continent has been so swept by foreign influence. Islam stretches not only across its top, but deep into the south as far as the lower reaches of the Belgian Congo. Northern Nigeria is as rigidly Moslem as Saudi Arabia, and political meetings in Guinea come to a halt at sundown, when everyone troops out, shucks shoes, and bows to Mecca. Throughout most of Africa the ubiquitous East Indian minority, tirelessly busy at trade and commerce, has also left its mark: the “European” towns of East Africa take more after Bombay than after any city in Europe. In Kenya a member of the Legislative Council may rise to speak, dressed in a skirt shaped after his Luo tribal costume of skins, but a flunky in knee britches and silver buckles carries a mace, as in the Mother of Parliaments.

“Ghanocracy Does Not Interest.”

The African leaders who cry so loudly for independence have also learned that, beyond a certain point, Africa's problems become not so much those between blacks and whites as between Africans themselves. For generations French West Africans have feared the Senegalese, who were the first to join the French in subduing them. The Senegalese in turn fear the lean, desert-dwelling Moors, who are fighting men with a long tradition of trading in slaves. In Houphouet-Boigny's Ivoiry Coast there have been recent race riots against African immigrants from Togoland and Dahomey.

The figure of Nkrumah no longer looms so large as it did, for Nkrumah's high-handed suppression of those who oppose him has offended other leaders. “Ghanocracy,” snorts Premier Mamadou Dia of Senegal, “does not interest us.”

And Premier Sylvanus Olympio of Togoland, on Ghana's border, wants to delay his own country's independence until Nigeria gets its in 1960, on the simple theory that Nigeria's 34.7 million people would never bow to Nkrumah's 4,800,000.

Nevertheless, however impractical it may sound at times, the yearning for a United States of Africa is real. Last month's creation of the Mali Federation —loosely encompassing the four former French territories of Senegal, the Voltaic Republic and the Republics Dahomey and Sudan—seems likely to be the pattern of things to come.

[Note. Just like the Ghana-Guinea union, the Mali Federation was short-lived. First, it shrank to two members (Senegal and Sudan), then it disintegrated in 1960, the year of its founding. — Tierno S. Bah]

The tide now running in Black Africa is toward independence, regional groupings, and a sort of African authoritarianism that pays its respects to Western democratic forms but rests on older habits of strong rule.

Though Touré's own constitution for Guinea carries a special article authorizing “the partial or total abandonment of sovereignty in the interest of African unity,” he himself has not made up his mind to join the Mali Federation. Yet, as the man who cut loose from France and has so far avoided the disaster that seemed bound to follow, he could well be the figure about whom an increasingly independent French West Africa would rally.

Africans are impatient at having their history written by others. Guinea's Minister of Education is already planning new textbooks to paint such heroes as Samory not as bloodthirsty savages, but as the Caesars and the Charlemagnes of Africa. Future texts will hardly be able to ignore the man of whom the jigging, clapping, Guineans sing:

Everybody loves Sékou Touré.

Independence is sweet;

Nothing is more beautiful than to be independent chez soi.

Vive Sékou Touré !

Vive Sékou Touré, our clairvoyant chief!

Note.

1. One of the “rules” was that no nation could set up a “sphere of influence” in Africa unless it had effectively occupied the area. Some immediate results: the Germans rushed into the Cameroons, driving the British merchants out; the British hastily set up the Oil Rivers Protectorate on the Niger Delta to keep the Germans out; the French sent garrisons into West Africa, occupied Conakry in 1897.